Coffee Break // Home Pen-Testing 001 // Cyber News 011

My experiments with pen-testing my home network continue… what is Cameradar? Can I use it to gain access to things I shouldn’t?

A café lungo with a few ounces of half-caf is my brew today. The flavor lacks a bit of body, but it came out nice and foamy which (if I’m being honest) was my main goal in combining the two.

//

Pen-testing progress.

Last night I had a couple of hours to spend more time learning pen-testing techniques with my authorized attempts to gain access to my family’s security system.

I had left off having determined that at least some of the security devices in question were accessible via the local network.

I spent some time doing a bit of research on the manufacturer of those devices in question, and performed a more detailed network scan of the specific IP address that was related to that company.

At this point in time, I was fairly certain that the device in question was a Network Video Recorder, the brains of the camera system and the place where all of the footage was being recorded to an SSD or HDD. I learned that most models of NVR from this manufacturer are designed to stream their video to a paired app over Wi-Fi.

Now that I know what I’m looking for… how do I get access to it?

I installed and toyed with the app in question for a few minutes, but quickly determined that there wasn’t really anything I could licitly do with it—after all, the manufacturer of the security cameras was not a participant in this pen-test.

If I was an actual attacker, I probably wouldn’t hesitate to set up an account with the app and see if I could brute force the username/password combination, or experiment with trying to capture the hash of an accounts password over the network.

However, I felt that anything that could potentially interact with the manufacturer’s servers would be unethical: while I feel perfectly comfortable searching for vulnerabilities in the products that my family owns and has authorized me to test, I have no authorization from the manufacturers of those products to test the security of their user account system or server infrastructure. I’m pen-testing my network; not theirs.

Since that attack vector was off the table, I uninstalled the app and returned my focus to the local network. Scanning the target IP with nmap again, I determined that it did in face have an open port that was configured to stream video from the cameras.

Ok, we’re back in the game. How do we gain access to that stream?

Many media players, like the popular VLC media player allow users to control video streams and save them as files, or stream them straight to the application. If I could find the MRL (think like a web address) of the stream, I could potentially get that video sent to VLC player on my computer.

But how to find the MRL? Enter Cameradar. A CLI tool built specifically for that purpose. Cameradar scans the target IP range for video surveillance cameras, and tries a library of default credentials and MRL/URL variations to find the camera’s log-on information and stream MRL.

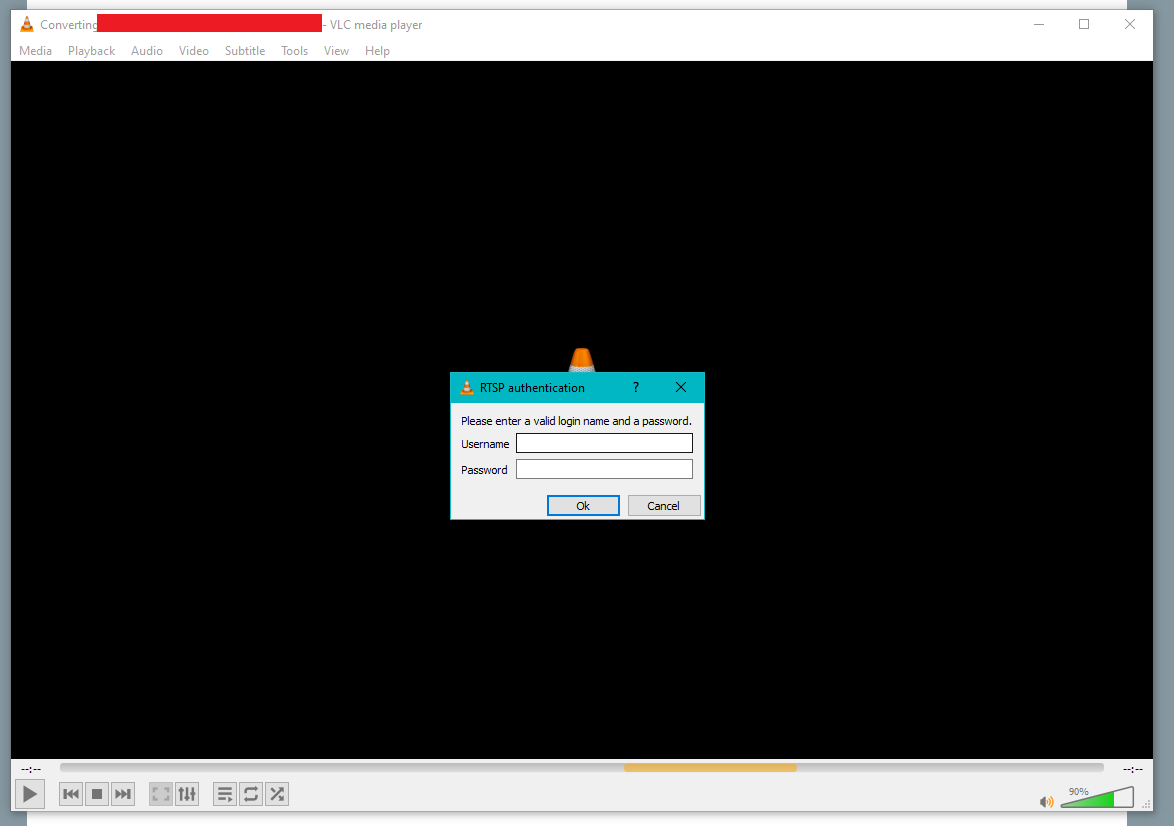

With the NVR’s stream MRL in hand, I plugged it into VLC Media player… but there was an issue:

The stream was password protected. I mentioned Cameradar could attempt to crack username/passwords—this is true, but it does not come with an extensive dictionary or username/password combinations to try. Maybe 12 dozen at most.

Still that might have been enough to gain access here, except for one key detail that I’m aware of:

This NVR is not using default credentials.

For my pen-test this is a roadblock, but for the security of my family’s network, this is excellent. One of the most commonly overlooked vulnerabilities when laymen set up their home networks is a failure to change default credentials. Here my family has been smart enough to change their credentials away from easily guessable defaults.

I may still be able to break into this stream with a good script for a dictionary attack, but for the moment at least my efforts are thwarted.

Next time I come back to this project, I’ll research a few more ways to try and exploit the stream, and then turn my attention to the other unsecured devices on the network—even if they aren’t something I can leverage to compromise the vulnerability of the whole network, I can at least harden them specifically against attack.

//

In the news.

Something I want to discuss from earlier in the week, is the debates surrounding ICE reporting apps. Apple and Google have come under some degree of fire for complying with government requests to remove apps like ICEBlock, an app for alerting other users of local sightings of ICE employees and operations.

The governments argument is that apps dedicated to that purpose have the potential to promote violence against federal employees and facilitate attacks against them. There may be some truth to that, but some are questioning if this is an exaggeration or double-standard..

After all, other apps (including Google’s own Google Maps) include the ability to report LE speed traps and so forth.

Should those apps also be taken down, or have those features removed? Or is it ethically legal and acceptable to alert other people to the presence of LE officials.

Now there can be no doubt that Apple and Google have every right to remove content from their store fronts if they deem it potentially hazardous or problematic in any way. Even if they apply a double standard to their content, I think that’s there right.

Still, I feel like this story brings up some downstream questions. What will happen if the next time an administration demands Google and Apple to take down an app, they refuse?

Coffee Break // Home Pen-testing 000 // Cyber News 010

The start of my home security pen-test.

I’m enjoying a café lungo this morning, with a slight breakfast of some toaster naan. Delicious—would that all the calories I eat in a day could be so toasty and savory.

The coffee is gone altogether to quickly… I consider another, but I should make myself some real food instead.

But first, let me share with you some details of a pet-project that I’m working on…

//

Penetration testing. (it sounds dirtier than it is)

Yesterday evening I spent around two hours setting up a penetration test of my family’s home security network. For those that don’t know, a penetration test is a legal, authorized attempt to compromise security frameworks in order to strengthen them.

Imagine if you put new locks on your doors, then challenged a lock-picking enthusiast to try and break in. If he’s able to get past the locks, or otherwise gain unauthorized access within the parameters you define, then you learn valuable information about where the vulnerabilities in your attack surface are, and how to mitigate or avoid that risk in the future.

Ok, that’s great, but how do we go about testing the security system in my family’s home?

First we define our objective. My goal is simple:

To gain remote access to the security cameras in the house, learning the administrator password or otherwise compromising the system by non-physical means.

Why non-physical attacks? A physical attack on the system is outside of the scope for this pen-test. I live inside the house in question—I’m literally inside of the system already.

What could I learn by walking across the house and unplugging the recorder? Nada.

So instead, we’ll see what we can leverage across the network. First stop: reconnaissance.

I boot up Virtual box. It’s a software for running emulations of computers and their operating systems. A computer inside of a computer…

Within virtual box, I boot up a Kali Linux image. This is a Linux distribution that comes preloaded with security and pen-testing tools, like Zenmap, the program you see here on the left.

On the right is Wireshark’s OUI look-up tool. More on that in a bit...

I boot up Kali Linux is because I don’t have many pen-testing tools installed directly on my Windows PC. Luckily, Kali Linux is chock full of them.

One of the tools I’m interested in trying out at this stage is Zenmap. Zenmap is a user interface for nmap, the command line port scanning and network mapping tool.

With Zenmap I make a list of IP addresses active on the network, and several open ports on these computers. TCP/UDP ports are like channels you can exchange information over the network with. Open ports are necessary for using the internet or your home network, but certain ports run more secure protocols than others, so leaving specific ports open potentially leaves your computer vulnerable to attack.

Think about if you locked all your doors, but forgot to lock your windows! All a burglar would need is a ladder and BAM he’s in.

After scanning the network with Zenmap for a while, I take note of a few vulnerable ports on one of the IP addresses I discovered. I’ll set that aside for now; I’m really only interested in mapping the network at the moment.

I want to find my target. To do that I need to look at the IP and MAC addresses of the devices on the system.

So, as it turns out, I don’t need really need Zenmap just yet. Just a terminal Window and Wirehsark’s OUI look-up tool will do.

Switching back to my main Window’s machine, I run an arp command to learn which IP and MAC addresses are associated on the network.

With that information in hand, it’s a simple matter to run each MAC address through Wireshark’s OUI lookup tool and identify the manufacturer for each device.

Conveniently for me, only one of them is associated with home security equipment.

Excellent; target acquired.

Unfortunately this was all the time I had for this project on Monday, but my next steps are clear: research the target device and probe it for any vulnerabilities.

I’ll post an update on this when I have time to progress the project later.

//

In the news.

In one week, the EU will vote on a proposed law that would enable governmental oversight of all communications on apps like Signal, basically bypassing the privacy guarantees of end-to-end encrypted services.

Signal indicates that it will not offer its services in Europe if the law changes. Speaking of Signal, the privacy leader is adding new encryption to it’s system that it says will be future-proofed against the rise of quantum computing. While that claim is untested, I think it’s good that companies are continuously investing in better and better encryption methods.

Since encryption stops an attacker from reading intercepted data, but not from recording it, advances in computation like quantum computing theoretically present a future vulnerability, where attackers will eventually be able to decrypt communications they captured but were unable to crack years ago.

Do you use Signal or other encrypted apps? Do you trust the end-to-end encryption they advertise?

In other news, I was mildly disappointed to see that popular communications and social forum app Discord (my go to for communicating with friends about hobbies) announced it had suffered a data breach through it’s customer support platform.

Evidently the stolen in formation included names/usernames, email and contact information, billing information, and message history with customer service agents.

Worryingly for those that reached out to Discord to settle age-verification issues, the government issued-ID they used to verify their accounts were also compromised.

I use Discord a lot in my day-to-day—it’s an important (albeit unsurprising) reminder that data breaches occur all the time, and if you had your information included in a breach yet, you likely will at some point.

It just goes to show, if you don’t want to risk information being leaked, don’t keep it in a digital format at all.